Review by: Úna Nic Cárthaigh

Darach Ó Scolaí’s latest novella brings readers to a small town on the west coast of Ireland in the first half of the 19th century. A time when oral tradition, poetry and music were central to communities and when Ireland and France had a unique literary relationship. In this particular town, poetry is very important and the story starts with the community eagerly awaiting the return of the schoolmaster who was representing the town at the poetry festival in Croom. However, when the schoolmaster returns with a face like thunder he announces ‘tá deireadh le héigse’. He is disillusioned with the old poetry and declares that he will write more true poetry from now on. As a result, we meet a cast of characters from this small town who are desperate to find a new representative for the poetry.

This is such a clever novel both in its fresh and original theme and the humorous and artistic way it is conveyed. It is clear that the author enjoyed playing with form and the historical timeline as he discusses not only the changes that came about poetry and the arts in Ireland at the time, but societal changes that began to happen. We see the power of the priest in society begin to wane and the lack of status for women as the people refused to send a female poet to the festival.

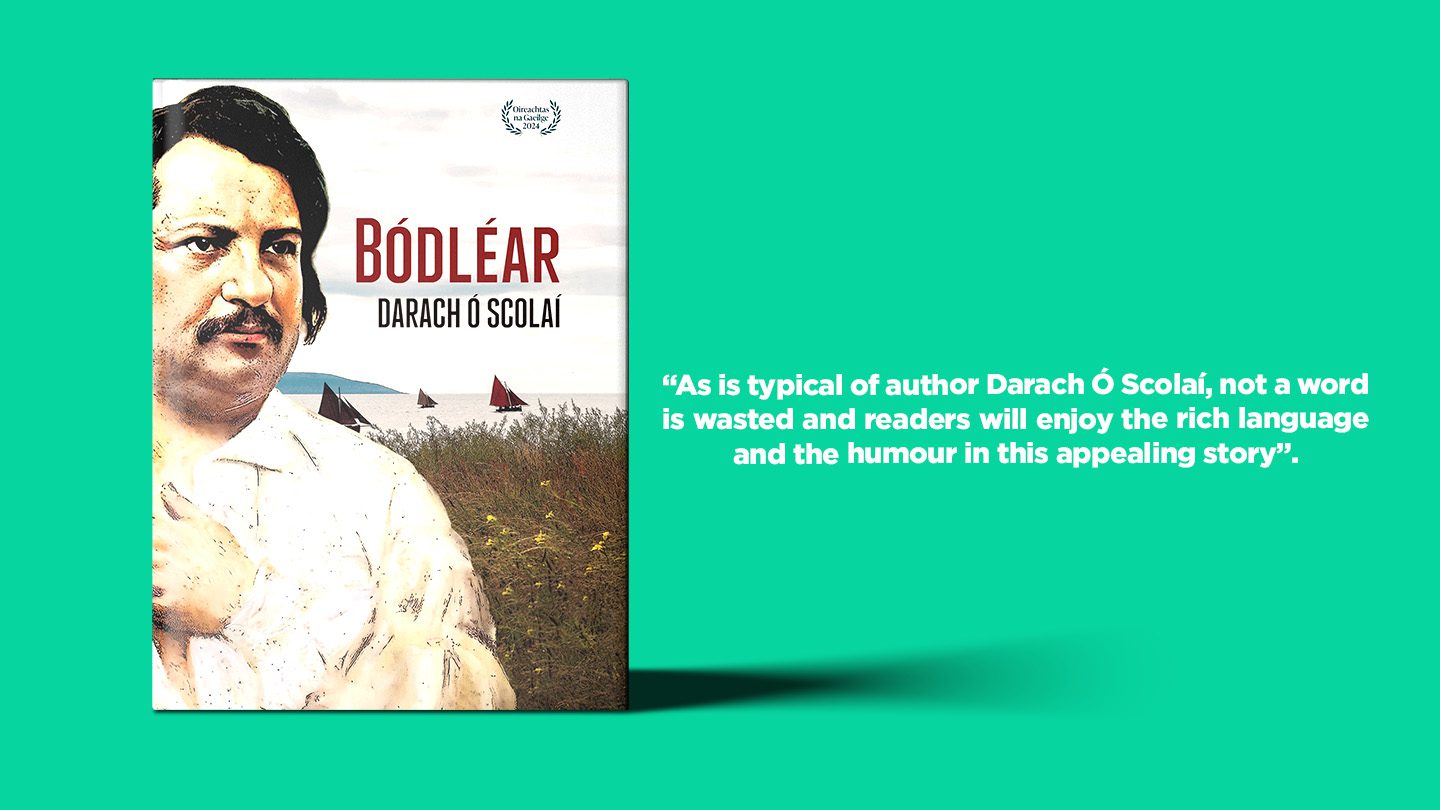

As is typical of author Darach Ó Scolaí, not a word is wasted and readers will enjoy the rich language and the humour in this appealing story. The world-building is powerful with artistic descriptions of the area which is ‘hung between mountain and shore’. From the very first page, readers are completely immersed in this vivid world.

There is great humour throughout, portrayed particularly well through the townspeople and their conversations with each other. As they desperately search for a new representative, the fights and conversations, gossiping and rumours are hilarious. We also see small-town behaviour with people trying to out-do each other in poetry and song, trying to hide their ignorance on things such as the meaning of the word ‘rancás’ and the purpose of the cafetiere that Bódléar gets delivered. There is a phenomenal richness of vocabulary to describe people in particular, for example we meet a ‘malrach seang buí faoi mhullach catach fionnbhán’, ‘aircín beag sagairt’ and ‘reanglamán fada mí-ásach amháin’.

Darach Ó Scolaí is a master at writing historical fiction and this novella is such a satisfying read. Will the schoolmaster manage to write truer poetry? Will the community nominate a new representative? Will anyone work out what the meaning of the word ‘rancás’ is? Readers will enjoy finding out this much and more in this gem.

Darach will have to make sure that he has enough space on the mantelpiece as Bódléar has received so much well-deserved praise and recognition since its publication. Not only did it win Gradam Uí Shúilleabháin (Book of the Year for Adults) at the Oireachtas Publishing Awards in September, but Darach lifted the award for best Irish Language Fiction Book (Gradam Love Leabhar Gaeilge Leabhar Ficsin Gaeilge na Bliana) at the An Post Irish Book Awards on the 27 November. More power to you, Darach!